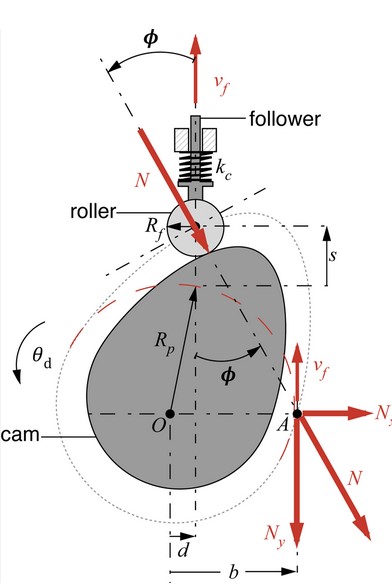

Figure

1: A cam-follower mechanism (From https://www.researchgate.net/publication/279290006_Nonlinear_Passive_Cam-Based_Springs_for_Powered_Ankle_Prostheses)

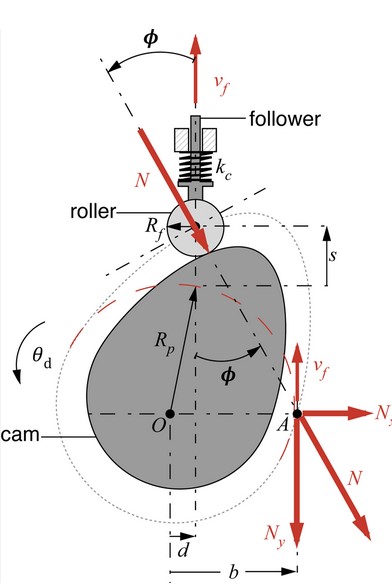

Figure

1: A cam-follower mechanism (From https://www.researchgate.net/publication/279290006_Nonlinear_Passive_Cam-Based_Springs_for_Powered_Ankle_Prostheses)

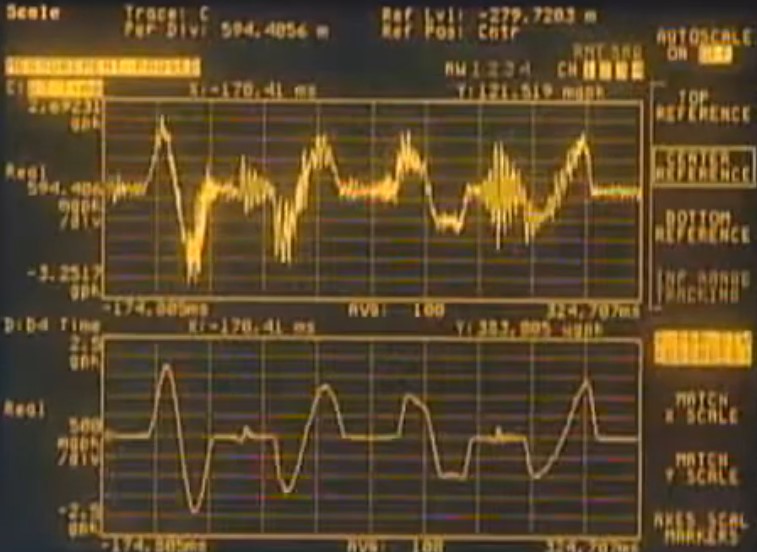

Figure

3: Cam-follower mechanism

acceleration curve (a) with noise (above) (b) with noise still present in

design but filtered out for display (below). (From https://youtu.be/NmQlarb7pzQ?si=Mr5TSVzQj-R6HBmf&t=732)